After a stroke at 24

Surgeons finally put Courtney’s skull back together. Then she had to put her life back together.

Chapter 1 Emergency

One weekend in May 2020, 24-year-old Courtney Chartrand was at her parents’ house in Winnipeg, helping them pack for a move. While Courtney packed books, her sister went to find a vacuum. When she returned seconds later, Courtney was on the floor experiencing a seizure.

“I don’t have any recollections of the rest until I got to the hospital,” says Courtney. Though she had few risk factors, doctors determined she had experienced a superior sagittal venous thrombosis, a rare type of stroke, with a large blood clot as well as bleeding in her brain.

Experiencing a stroke at any age is scary. But Courtney’s occurred during the height of the first wave of COVID-19, which meant she was alone in hospital, without her husband, Collin, or her parents by her side.

She struggled to understand and remember what her healthcare team was telling her. “I wasn't able to pass it on to my family and I wasn't able to retain it for my own healing. It was an endless loop of discouragement.”

And frightening skull removal surgery added to the fear Courtney and her family were already experiencing.

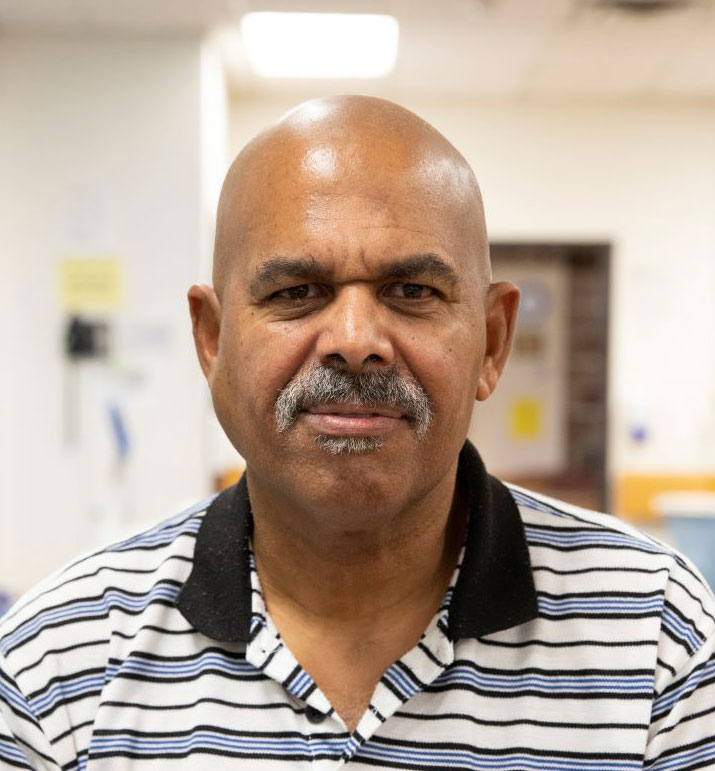

Doctors stapled Courtney’s scalp back in place, after a piece of her skull was temporarily removed.

Courtney and her family: Her siblings Reis and Ryan, dad Bob, mom Candace and husband Collin.

After Courtney's skull was restored by surgeons, she celebrated by taking a sledgehammer to her helmet.

Courtney and her husband, Collin, celebrate after completing a triathlon event.

Chapter 2 Relieving pressure as the pandemic added more

Courtney’s brain was dangerously swollen, and it wasn’t coming down. To relieve the pressure, doctors decided to temporarily remove a piece of her skull.

They stapled her scalp back in place, but beneath it there was no bone, just brain. And the surgery to replace her skull was delayed, partly due to COVID-19 disruptions. So Courtney had to wear a custom pink helmet to protect her brain. But it meant she could go home.

Life without half her skull required adaptation. Courtney’s mother had to wash her hair; doing it herself brought on a headache that lasted for days. Finally, after three months, surgeons restored her skull. Courtney celebrated by taking a sledgehammer to the pink helmet.

But recovery, both mental and physical, would take longer. “I didn't understand why I couldn't walk and why I couldn't think and why I was so easily agitated. Like it didn't make sense to me.”

During her time in outpatient rehabilitation, Courtney developed strategies to get the care she needed despite COVID-19 restrictions. “I had to jump through hoops for every doctor that I visited to make sure that I could bring someone with me.”

After borrowing her grandmother’s wheelchair and walker to learn to walk again, Courtney continued to make progress.

Her father-in-law gave her his old bike, and she soon fell in love with cycling. With her balance uncertain at first, Collin would walk beside her as she pedalled. As she gained confidence, he rode alongside or behind her. “I wasn't alone, but I was stable by myself,” she says. “I worked my way up from there.”

Emotional adjustments proved harder. Courtney was angry at first about everything she had lost, including work she loved as a primary teacher.

She also lost some friendships with people who did not understand that although she looks the same, she is a different person inside — one who often struggles to find words and who needs frequent rest to preserve her energy.

Chapter 3 New priorities, new peace

Courtney now lives with epilepsy and has the occasional seizure but is otherwise back to pre-stroke health. She’s worked hard to make peace with priorities, making space for some that have changed completely. “Life is so short and fragile,” she says. “I’m not wasting my time on things that I don't want to do.”

Courtney has been embracing mindfulness, movement and new experiences. When Collin wanted to compete in a triathlon event and asked her to be his partner, she thought, why not? “I figured he's done all this for me. I can try for him. And if I need to stop and walk, or if I need to take a break, I don't care.” Courtney completed the race — and had a lot of fun doing so.

Courtney now works as a crisis lines counsellor and coaches crisis line volunteers. “I love getting to feel like I’m making a difference and empathizing with people who are struggling. That resonates with me,” she says.

She’s ever-grateful for her husband’s unwavering support, and her family, for being with her every step. “They’re incredible,” she says. They attend appointments with her, help advocate for her health and remember the small details. They’ll even remember special anniversaries, like the day she smashed her helmet.

“Sometimes, I feel like they forget that my brain is not the same,” she expresses. Courtney says that even though she might look the same, she still struggles with memory and hierarchical thinking. “I’ve learned I need to have a lot of patience with myself. Something I need more practice with.”

Courtney calls her stroke a blessing. “It gave me perspective. I don't look that far forward anymore. I want to live today fully before I start worrying about tomorrow.”

More stories

Tackling the emotional impacts of stroke

Dr. Swati Mehta helps people embrace an altered future

Giving up is not in my vocabulary

With his wife by his side, Michael is determined to beat stroke.

Taking aim at a key cause of dementia

Dr. Philip Barber uses machine learning to take aim at vascular cognitive impairment