Immune system could hold key to preventing heart attacks

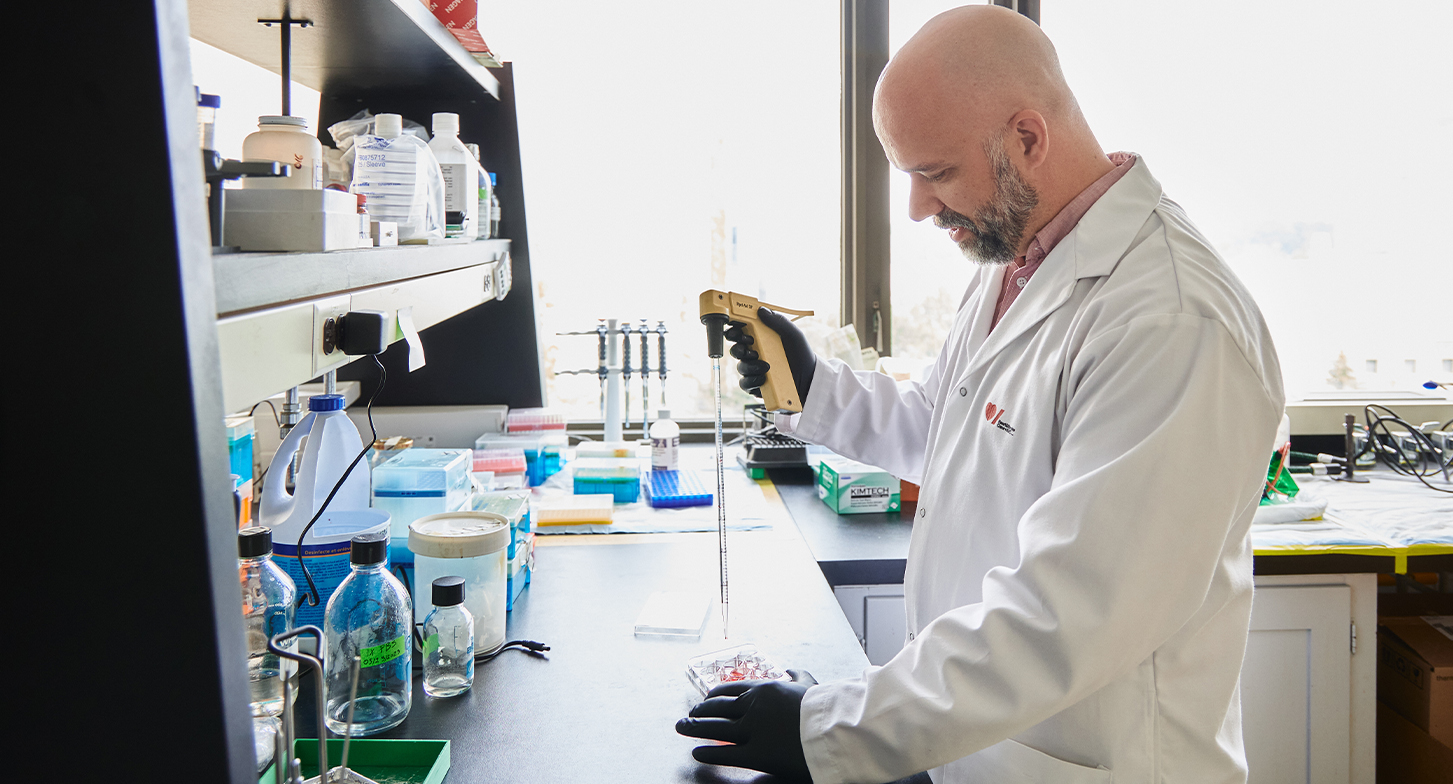

Dr. Bryan Heit unlocks genetic secrets to target atherosclerosis

Chapter 1 Immune cells going rogue

“We're ultimately trying to find ways to manipulate the immune system in a way that reverses atherosclerosis,” Dr. Bryan Heit says.

The most common type of heart disease happens when clumps of fatty plaque buildup inside blood vessels in your heart. Those clumps can rupture, blocking blood flow and causing a heart attack.

But how does this plaque, called atherosclerosis, build up in the first place? Could we stop it from happening? These questions are far from simple, and Dr. Bryan Heit is on the hunt for answers.

Dr. Heit, an associate professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Western University in London, Ont., describes atherosclerosis as an immunological disorder. “When cholesterol deposits start to build up in blood vessels of your heart, your immune system sounds the alarm and brings cells called macrophages to clean up the mess.”

In about half of us, that cleanup fails. “The macrophages, instead of cleaning up that cholesterol, start to accumulate and die,” Dr. Heit explains. More macrophages arrive to help, but eventually die and add to the mess.

“A plaque is just a mass of dead and dying macrophages,” Dr. Heit says. “All the lipids and cholesterol that they’ve taken up kind of spill out into the tissue. And this is occurring right below the lining of our blood vessels in the heart.” This can lead to heart attack.

Dr. Heit is targeting a specific gene, GATA2, which could be the key to preventing atherosclerosis.

Dr. Heit’s team is also studying other genes that may be activated by GATA2 and the signals that turn it on.

Dr. Heit’s research was made possible by Heart & Stroke donors.

Dr. Heit is working to discover what triggers this negative cycle — what he calls “macrophages behaving badly” — then find ways to disrupt it.

Chapter 2 On the cusp of discoveries

Dr. Heit’s quest got a kick-start from Heart & Stroke donors, who supported him with a post-doctoral fellowship at the beginning of his research career in 2009. “That’s really when I started working on atherosclerosis-relevant research.” His Heart & Stroke funding continues today through grants. And it’s producing results.

In 2020, Dr. Heit’s team identified a gene that is expressed by macrophages as they move into the heart to clean up cholesterol.

“This gene, called GATA2, seems to be turned on to help the macrophages deal with the stress of cholesterol,” he explains.” But the consequence is that macrophages then become bad at cleaning up dead cells.” GATA2 also triggers the macrophages to divide, adding to the problem.

“We’re very interested in looking at whether targeting GATA2 might be a way of preventing all that from happening.”

To study this, Dr. Heit and his team use tissue samples and blood from people undergoing bypass surgery. They’re looking for other genes that may be activated by GATA2, and for the signals that turn on GATA2 in the first place.

To use the small samples efficiently, they created a sort of honeycomb vessel using 3D printing. It has 32 tiny compartments on a single laboratory slide - about the size of three postage stamps side by side. This allows them to do dozens of different tests on a small number of cells, adding testing agents, then examining the results under a microscope.

Previously, each test would have been done in a dish 35 millimeters in diameter (about the size of a golf ball), requiring hundreds of thousands of cells.

“Using human samples may give insights that can’t be seen in animal models such as mice,” Dr. Heit says. “A big element of atherosclerosis that's missing from most models is something called ‘inflammaging’.

As we age, our immune systems change, and they become more prone to inflammation, which would include atherosclerosis. We have some evidence that this expression of GATA2 is probably associated with age.”

Chapter 3 Medication could save lives

Dr Heit is excited about the possibility of one day targeting GATA2 with medication. There are drugs already in clinical trials, but these trials involve blood cancers, in which GATA2 also plays a role. It’s not yet clear whether they would work in people with atherosclerosis.

Dr. Heit is hopeful that GATA2 medication could become a powerful new weapon against atherosclerosis, but controlling cholesterol will still be critical. This has been greatly improved by advances over decades, including some by Heart & Stroke funded researchers.

“The cholesterol-reducing drugs work really, really well for patients who have severe heart disease,” Dr. Heit says. His solution, targeting GATA2, could help people at earlier stages by treating atherosclerosis before it becomes advanced.

To get there, Dr. Heit says, Heart & Stroke support is playing a crucial role. “It has allowed us to pursue this project, which is higher-risk.”

It’s a risk that could bring powerful rewards one day, measured in heart attacks prevented and lives saved.

- Learn more about recovering from heart disease.

- What we know about preventing Heart attack.

- Understanding risk for high cholesterol.

Join the fight to end heart disease and stroke.

Real stories

Preventing stroke before it strikes

Research by Dr. Jodi Edwards could head off the factors that increase risk – especially for women

Samantha’s fight for every word